Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment

Volume 2: Personality Assessment

Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Volume 2: Personality Assessment Mark J. Hilsenroth (Editor), Daniel L. Segal (Editor), Michel Hersen (Editor-in-Chief) ISBN: 978-0-471-41612-8

September 2003

Table of Contents

Part Three: Overview, Conceptual, and Empirical Foundations

23 Projective Assessment of Personality and Psychopathology: An Overview 283 Mark J. Hilsenroth

24 Projective Tests: The Nature of the Task 297 Martin Leichtman

25 The Reliability and Validity of the Rorschach and Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) Compared To Other Psychological and Medical Procedures: An Analysis of Systematically Gathered Evidence 315 Gregory J. Meyer

CHAPTER 23 Projective Assessment of Personality and Psychopathology: An Overview

MARK J. HILSENROTH

HISTORICAL, THEORETICAL, AND PSYCHOMETRIC OVERVIEW 283 SPECIFIC INSTRUMENTS 286 SPECIFIC CONTENT AREAS 288

HISTORICAL, THEORETICAL, AND PSYCHOMETRIC OVERVIEW

Projective methods of personality assessment provide the clinician with a window through which to understand an individual by the analysis of responses to ambiguous or vague stimuli. These methods are generally unstructured and also call on the individual to create the data from his or her personal experience. An individual’s response(s) to these stimuli can reflect internal needs, emotions, past experiences, thought processes, relational patterns, and various aspects of behavior. Moreover, projective methods involve the presentation of a stimulus designed to evoke highly individualized meaning and organization. No limits on response are arbitrarily set, but rather, the individual is encouraged to explore an infinite range of possibilities in relating his or her private world of meanings, significance, affect, and organization (Frank, 1939).

It will suffice to say that while the instruments may differ, the results of these methods provide ready access to a variety of rich conscious and unconscious material. An important SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND SETTINGS 290 APPLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS 292 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES 292 REFERENCES 293

aspect of projective stimuli is their ability to provide information about thoughts, actions, and emotions. Also, the process of generating associations across different levels of meaning can aid in understanding an individual’s cognitive structures, the elements of which may often be disparate. The responses to these stimuli can also be a vehicle for understanding how someone experiences his or her world and conveys those experiences to others. These responses occur as a representation, through various mediums, of an individual’s personal experience such as narratives (i.e., storytelling) and the perception of visual images. The manner by which people create images and organize language, affective expressions, or perceptions is seen to be highly personal. These modes of responding can reveal patterns of that individual’s thought, associations, and experiences. It is in this capacity of exploring perceptual acuity, as well as interpersonal and affective themes, that the interpretation of projective material has been most utilized by clinicians in the past.

Many clinicians who utilize these free response or unstructured methods of assessment have expanded upon the initial theoretical conceptualization of this “projective response process” beyond a psychoanalytic paradigm to include ego psychology (Bellak & Abrams, 1997), constructivism (Raskin, 2001), perceptual-cognitive style (Exner, 1989, 1991, 1996), experiential factors (Lerner, 1992; Schachtel, 1966), explicit and implicit processes (McClelland, Koestner, & Weinberger, 1989), as well as process-dissociation (Bornstein, 2002) perspectives. The plurality of different theoretical perspectives from which to understand projective material is a significant benefit for those who would use these techniques.

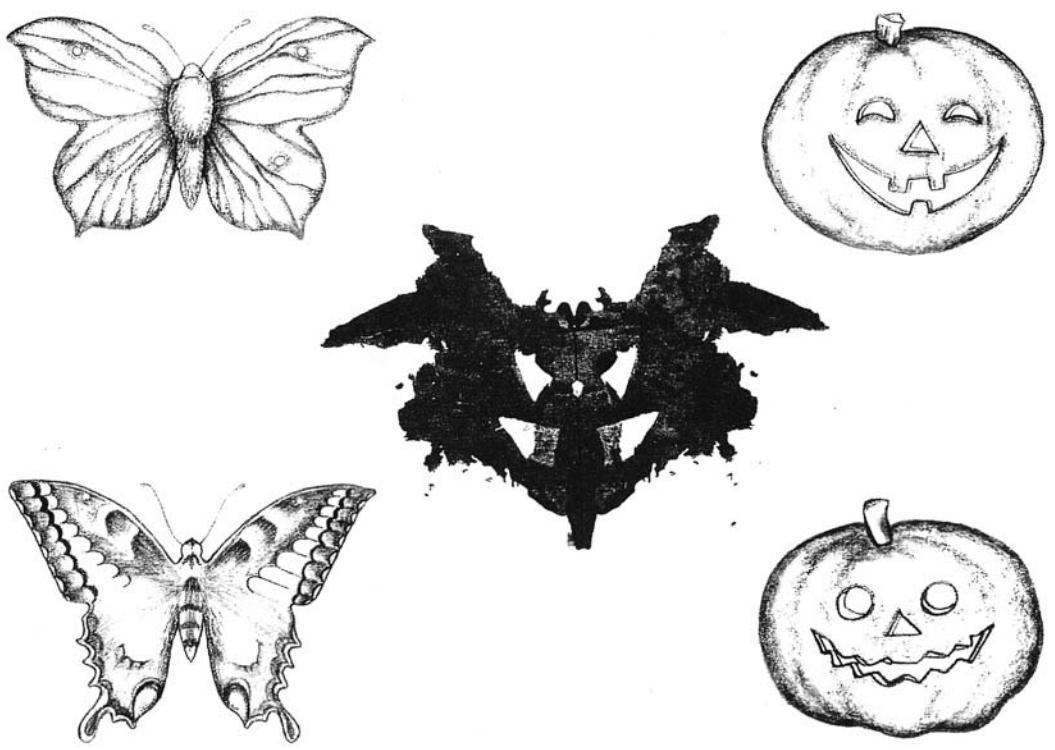

This section begins with one such chapter by Leichtman that provides a compelling conceptualization of projective tasks. Leichtman’s chapter (Chapter 24) reviews traditional conceptions of the projective task and their limitations. First, Leichtman presents evidence for an alternative theory centering on the concept of representation and explores the roles of four key components in this response process. Second, he discusses the representational act (i.e., the sense of self, the audience, the use of the symbolic medium, and the referent) in the test response process. Finally, he concludes with an examination of the way in which this conception of the task provides a framework for understanding what unites projective instruments as a class, what differentiates them from one another, how their interpretation has been approached, and what are their inherent strengths and drawbacks.

A second important issue related to the theoretical conceptualization of these tests is their place in a multimethod assessment paradigm. Often, psychological assessment occurs along one modality, which limits application of results and restricts the extent to which data can be generalized to both clinical and research applications. In any psychological assessment, one needs to allow for problems of disorder differentiation, comorbidity, sampling from a range of different severities, symptom overlap, and complexity of that individual. The importance of a multitrait-multimethod approach to assessment has been stressed by a number of different authors (Campbell & Fiske, 1959; Jackson, 1971; Leary, 1957; Rapaport, Gill, & Schafer, 1945). Implicit in this approach is the idea that individuals are multidimensional beings who vary not only from one another but also in the way others view them (social perception), the way they view themselves (self-perception), and the ways in which underlying dynamics will influence their behavior (motivation/meaning/fantasy/ ideals). Such an approach presents clinicians and researchers with the responsibility to sample from each domain of functioning. This form of assessment may aid clinicians in obtaining a comprehensive understanding of an individual rather than focusing on just one facet of behavior. Also, various forms of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed. [DSM-IV]; American Psychiatric Association

[APA], 1994) Axis I and II psychopathology have frequently been viewed as multidimensional and, therefore, a single score on any one measure may be far less optimal than an assessment process that provides information concerning the multiple aspects of a given syndrome (i.e. narcissistic pathology reflected in grandiosity, need for mirroring or admiration, narcissistic rage, entitlement, etc.). It seems prudent to encourage clinicians and researchers alike to employ multiple methods of assessing various forms of psychopathology and to utilize this information in a systematic and theoretically consistent fashion. The goal of this approach to diagnosis is to connect both the surface (readily apparent in behaviors) and deeper (intrapsychic) manifestations of any disorder in a conceptual manner, in order to generate clinical and dynamic signs that may be used reliably for differential diagnosis.

One of the issues related to this need for a multimethod psychological assessment faced by applied clinicians on a daily basis is what many in social and personality psychology have come to call self-report bias. A substantial body of experimental research has demonstrated that individuals exhibit a defensive bias when asked to self-report aspects of their personality or psychopathology. For example, individual differences in self-serving biases have been demonstrated in relation to attributions, self-descriptions, inferences, personality traits, and avoidance of negative affect (Block, 1995; Colvin, Block, & Funder, 1995; Dozier & Kobak, 1992; Funder, 1997; John & Robins, 1994; McClelland et al., 1989; Ozer, 1999; Shedler, Mayman, & Manis, 1993; Viglione, 1999; Weinberger, 1995). The presence and importance of intrapsychic, unconscious, implicit, automatic, private, or internal personality characteristics suggest that projective test variables may prove to be very useful when employed in tandem with other methods of assessment that are designed to assess more overt, direct, conscious, or behavioral expressions of psychopathology.

An assessment using measures that evaluate both intrapsychic as well as interpersonal and behavioral aspects of personality is optimal and provides clinicians with a richer understanding of individuals. This multidimensional assessment may be especially salient given that self-report inventories concerning the assessment of Axis I and Axis II tend to be more direct (i.e., obvious) in identifying symptoms and therefore are susceptible to malingered or defensive responses. Moreover, many clinical patients (i.e., patients with schizophrenia, delusional disorder, or personality disorder) are particularly unable to view themselves in a realistic manner. Interviews may allow for greater flexibility in the assessment of personality and psychopathology because clinical judgment may be necessary to determine or clarify whether the diagnostic aspects of a patient’s behavior are present (e.g., DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder [NPD] Criterion 9: Arrogant and haughty behaviors). While interviews allow for the clinical observation of behavior, one has to wonder if this same criticism might also apply, at least in part, to semistructured interviews. Additionally, interviews have limitations of which clinicians should be well aware. Past research has indicated that clinicians may underestimate or minimize coexisting syndromes once the presence of one or two Axis II disorders has been recognized (Widiger & Frances, 1987). Unlike self-report inventories, which may include indices that detect intentional response dissimulation (faking), exaggeration of symptoms, random responding, acquiescence, or denial, clinical interviewers may be susceptible to active attempts at malingering. Assessment of Axis I and Axis II criteria may be difficult through direct inquiry and, therefore, it is questionable whether many patients would admit that they are, for example, egocentric, self-indulgent, inconsiderate, or interpersonally exploitive.

Perhaps because the scoring and interpretation of responses to projective techniques can be perceived by those unfamiliar or untrained in their use as less obvious or directly related to salient clinical issues, these methods have at various times come under harsh criticism (Dawes, 1994; Eysenck, 1959; Jensen, 1965; Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000; Peterson, 1995; Wood, Nezworski, & Stejskal, 1996). In fact, some psychologists have promulgated such unrealistic clinical utility criteria for projective assessment instruments (Hunsley & Bailey, 1999, 2001) that the unbiased implementation of such standards across various methods of psychological evaluation would result in abandoning all testing, interviews, and observation for assessment. A subsequent extension of these criticisms has been a series of unrealistic calls for a moratorium on the use of some instruments (Garb, 1999; Garb, Florio, & Grove, 1998; Garb, Wood, Nezworski, Grove, & Stejskal, 2001). However, these recent criticisms are clearly contradicted by empirical findings; are flawed by the use of methodological double standards; and suffer from confirmatory bias and incomplete coverage of the literature. In addition, the critics fail to integrate positive contributions that have specifically addressed earlier criticisms and, most figural, they present no original data to support their positions (see Meyer, 1997a, 1997b, 2000, 2001; W. Perry, 2001; Viglione & Hilsenroth, 2001). Finally, these attempts to criticize and limit projective assessment occur in direct contradiction to recent evidence from clinical training, practice, and research (Bornstein, 1996, 1999; Camara, Nathan, & Puente, 2000; Clemence & Handler, 2001; Eisman et al., 2000; Hiller, Rosenthal, Bornstein, Berry, & Brunell-Neuleib, 1999; Meyer & Archer, 2001; Meyer et al., 2001; Meyer et al., 2002; Rosenthal, Hiller, Bornstein, Berry, & Brunell-Neuleib, 2001; Stedman, Hatch, & Schoenfeld, 2000; Viglione, 1999; Viglione & Hilsenroth, 2001; Weiner, 1996, 2001).

In the most recent analysis of extant validity data, Meyer and Archer (2001) provide a definitive response regarding the clinical utility of one projective technique, the Rorschach (Rorschach, 1921/1942), within the context of other psychological assessment instruments. After providing extensive validity data comparing the Rorschach with both intelligence (i.e., Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [WAIS]; Wechsler, 1997) and self-report measures of personality (i.e., Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory [MMPI]/MMPI-2; Butcher, Dahlstrom, Graham, Tellegen, & Kaemmer, 1989) these authors offer the explicit conclusion that “there is no reason for the Rorschach to be singled out for particular criticism or specific praise. It produces reasonable validity, roughly on par with other commonly used tests” (pp. 491–492). Meyer and Archer (2001) further note that validity is always conditional, a function of predictor and criterion, and that this limitation poses an ongoing challenge for all psychological assessment instruments.

Meyer provides an additional broad overview chapter (Chapter 25) of psychometric evidence for performance-based (i.e., projective) personality tests, with a primary focus on the Rorschach and Thematic Apperception Test (TAT; Murray, 1943). To contend with potential interpretive biases, psychometric data are drawn exclusively from systematic metaanalytic reviews and presented along with the evidence for alternative measures in psychology, psychiatry, and medicine so readers can compare results across areas of applied health care. The results from 184 meta-analyses on interrater reliability, test-retest reliability, and validity reveal that the psychometric evidence for the Rorschach and TAT is similar to the evidence for alternative personality tests, for tests of cognitive ability, and for a range of medical assessment procedures. As such, the evidence suggests that the Rorschach and TAT should continue to be used as sources of information that are integrated with other findings in a sophisticated and differentiated psychological assessment.

The analyses presented by Meyer address several issues in a very detailed manner and one could reasonably wonder whether such extensive analyses are necessary. However, despite prior meta-analyses (Atkinson, Quarrington, Alp, & Cyr, 1986; Bornstein, 1996, 1999; Hiller et al., 1999; Meyer, 2000; Meyer & Archer, 2001; Meyer & Handler, 1997; Meyer et al., 2001; Parker, Hanson, & Hunsley, 1988; Rosenthal et al., 2001), several critics have continued to claim that projective assessment reliability and validity remain poor or inadequate. Viglione and Hilsenroth (2001) have pointed out important problems and inconsistencies in the arguments of those critical of projective techniques and have reviewed evidence at

the individual study level indicating reliability and validity issues are sound. The detailed findings reported by Meyer should serve to further solidify this evidentiary foundation.

SPECIFIC INSTRUMENTS

Each of the next seven chapters describes a specific test and reviews current psychometric data, research findings, and the clinical utility of the measure. Weiner (Chapter 26) discusses the current status of the Rorschach. His chapter reviews the conceptual basis of the measure and summarizes current research findings, psychometric characteristics, and clinical practice trends. Weiner also discusses the utility of Rorschach applications, the admissibility of Rorschach testimony into evidence in legal cases, cross-cultural considerations in Rorschach assessment, and the computerization of Rorschach results, as well as the current and future status of the instrument. Cumulative research findings presented by Weiner document that the Rorschach can be reliably scored; that it shows good test-retest reliability; and that the effect sizes found in correlating the Rorschach with external criteria are equivalent to those found for the MMPI or MMPI-2 and demonstrate as much validity as can be expected for personality tests. Because Rorschach assessment facilitates decision making that is based on personality characteristics, the Rorschach is frequently found useful in the practice of clinical, forensic, and organizational psychology, particularly with respect to such matters as treatment planning. Survey data and research presented indicate that the Rorschach is widely accepted in the courtroom and is culturally fair in its applicability to diverse national and ethnic groups. Software programs are available to assist in the scoring and interpretation of Rorschach protocols. Although reservations have been expressed in some quarters about the validity and utility of Rorschach assessment, available evidence indicates that there is sustained interest among knowledgeable assessment psychologists in using the Rorschach and conducting research with it.

The Moretti and Rossini chapter (Chapter 27) reviews the origins and development of the Thematic Apperception Test. It has been used continuously as a lifespan projective technique in clinical assessment and personality research for nearly 65 years. The TAT, similar to the Rorschach, has retained its popularity despite the psychometric challenges of critics (Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000). The authors provide evidence that the TAT can indeed be used in psychometrically satisfactory ways. The authors also recognize potential limitations in that some TAT research is limited to single or small sets of variables, as seen in the more recent development of

clinically relevant and empirically adequate coding systems that are intentionally very limited in scope. Such coding systems build upon the rich tradition of the measurement of individual or social motivation and their correlates. A distinctive aspect of this chapter is that it suggests a more applied use of the TAT as a semistructured technique in clinical settings. The role of clinical personality assessment using the TAT is better understood as generating an understanding of the patient’s inner world, situational issues, and dynamics that will hopefully advance the therapeutic process. These authors also recommend using the TAT directly within the psychotherapeutic setting to explore the experience-near nature of the instrument. In addition, the use of empirical and clinically relevant coding systems (e.g., Social Cognition and Object Relations Scale [SCORS]; Westen, 1995) are reviewed. Issues regarding cross-cultural investigations, card selection, narrative recording, and appropriate reeducation concerning the theoretical aspects of the technique (e.g., Rossini & Moretti, 1997) are discussed.

Sentence completion tests (SCTs) are commonly used techniques in adult personality assessment. The chapter by Sherry, Dahlen, and Holaday (Chapter 28) highlights the variety of SCTs that have been developed over the years and provides substantial information about the Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank (RISB; Rotter, Lah, & Rafferty, 1992), the most widely used SCT. Following an overview of the history of SCTs, the RISB is described in terms of its theoretical rationale, its development, and its psychometric properties. Discussion then broadens to the range of applicability and limitations of SCTs in general, addressing their use with diverse populations and persons with disabilities. The chapter also discusses the use of SCTs with computers, research, and the future of SCTs. This particular review is distinctive in that SCTs are reviewed in general and a comprehensive table of over 40 SCTs found in the literature is provided including the name of each test, the purpose or theory of the SCT, and the original citation for each test. The authors recommend that SCTs be utilized more fully in clinical settings as meaning-making exercises for both the assessment and facilitation of the therapeutic process.

The primary focus of the Handler, Campbell, and Martin chapter (Chapter 29) is the review and integration of research as well as clinical methodology for the Draw-A-Person Test (DAP; Machover, 1949), the House-Tree-Person Test (H-T-P; Buck 1948), and the Kinetic Family Drawing Test (K-F-D; Burns & Kaufman, 1970). The chapter includes a brief introduction and description of each test, including administration instructions. The particular advantages and disadvantages of each test are also discussed. Special attention is given to the effects of culture on each of the three instruments. Information is also supplied to assist the reader in critically evaluating each test in terms of its applicability, as well as information concerning its limitations in clinical application. One unique contribution of the chapter is that it relates early research and conceptualization concerning graphic assessment techniques to more recent findings. A second unique contribution concerns the evaluation of much past validation research design as oversimplified and as inappropriate, necessarily leading to negative findings. Instead, the recommended validity research approach is a design that is most similar to the way(s) in which graphic techniques are used in clinical assessment. The chapter discusses validity research findings from the use of an experiential paradigm in which a clinically focused phenomenological approach has resulted in significant positive results for graphic techniques. The chapter also discusses the detection of emotional problems through the use of an integrated constellation of variables and describes several welldesigned validity studies, as well as the need for detailed normative data on gender and cultural subgroups.

The history, theoretical basis, and development of the Hand Test (Wagner, 1983) are reviewed by Sivec, Waehler, and Panek (Chapter 30). The scoring system of this measure is presented and the psychometric properties (i.e., interscorer agreement, norms, reliability, and validity) of the test are evaluated, based upon current psychometric standards. Summaries of Hand Test research are provided for individuals diagnosed with mental retardation and for older adults. In contrast to previous reviews that organize Hand Test data according to clinical or diagnostic groups studied, the current review represents a comprehensive effort to organize and evaluate research data according to scoring category. This approach allows the reader to review relevant data for specific scores. In addition, this chapter provides the first comprehensive review of the Hand Test literature since the revised manual was published in 1983. Recommendations for use of the Hand Test in clinical and organizational settings are provided. In this regard, the Hand Test has consistently shown its utility as a measure of psychopathology and actingout behavior. In addition, certain Hand Test variables have been associated with specific clinical disorders. The extensive use of the Hand Test in several diverse cultures leads to the suggestion for an international Hand Test manual. Updated norms and further investigation of the Hand Test with specific diagnostic groups is also recommended.

The chapter by Fowler (Chapter 31) reviews the historical, theoretical, and empirical foundations of applying thematic and content analysis to patient narratives of their earliest childhood memories in order to obtain information regarding a wide array of clinically relevant issues (i.e., personality types, degree of psychological distress, aggressiveness, substance abuse, object relations, and affect). In addition, the assessment of adolescent and child psychopathology as well as the use of early memories to evaluate treatment outcomes are reviewed. Based upon available empirical evidence, it appears that early childhood memories can be a useful and reliable tool for assessing some aspects of psychological functioning. This would include the estimation of personality types, the assessment of potential aggressiveness and substance abuse as well as the quality of object representations and affect tone. Empirical studies demonstrate that clinical judgments and scoring systems for early memories can substantially improve our understanding of defensive denial and its impact on physiological functioning. This finding further demonstrates that projective techniques can be utilized to supplement selfreport measures of distress and psychological disturbance. Although limited, data from outcome studies seem promising for the use of early memories as a measure of internal change, but the lack of norms and test-retest reliability data currently limit these findings. In addition, Fowler addresses potential areas of concern such as the preference of investigators creating new scales to assess an ever-expanding array of psychological functions, rather than developing a program of systematic research to replicate and build on previous studies. However, in recent years several scoring systems have been proposed to integrate and standardize administration and scoring. The author concludes by noting that further work is required in order to validate specific scoring systems, especially studies that replicate initial findings utilizing existing systems.

The last chapter in this section on specific measures presents a new test that examines the intersection of attachment theory and projective assessment through the lens of the Adult Attachment Projective (AAP; George, West, & Pettem, 1999). The AAP is a new assessment technique that emphasizes the role of defensive processes in the organization of individual differences in attachment status. The chapter by George and West (Chapter 32) begins with a discussion of the attachment concept of defense as conceptualized by Bowlby’s attachment theory (1980). The chapter then describes the AAP, providing an overview of the coding system and validation data for this new measure. The authors then return to the topic of defenses, using AAP story examples to highlight how Bowlby’s conceptualization of defensive exclusion differentiates secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and unresolved attachment status in adults. With the projective assessment of adult attachment as the frame of reference, the chapter describes the intricacies of defensive operations, the analysis of projective story content, and discourse that differentiates among representational patterns of attachment. The chapter concludes with a discussion of how projective methodology is consonant with attachment theory and, as demonstrated through the AAP, contributes to new insights regarding attachment theory and research. The chapter makes a unique contribution to the literature in that it presents a new tool that to date has been demonstrated to be a valid assessment of individual differences in adult attachment representation. Furthermore, these authors provide a new perspective regarding the role of defensive exclusion as it functions in adult attachment representations as well as clinical examples of attachment representations.

SPECIFIC CONTENT AREAS

Projective techniques allow clinicians to study samples of behavior collected under similar conditions in different native languages around the world (e.g., Bellak & Abrams, 1997; Erdberg & Schaffer, 1999, 2001). There is an efficiency to sampling behaviors with such techniques to develop one’s understanding and appreciation of developmental changes across the age span and across all types of disorders and problems. In addition, the variety of scoring systems for different measures addresses a wide range of clinical, personality, forensic, developmental, cognitive, and neuropsychological constructs. For example, the Rorschach allows one to develop a common, experientially based database for the problem-solving practices and internal representations of clients from age 5 through old age. One could identify many other single purpose scales within a specific content or construct area that might compete well with the Rorschach, but to produce the same benefits one would have to master and monitor developments in perhaps 100 alternative instruments. To make cost-benefit comparisons ecologically valid, one would have to envision a full range of cost and benefit equivalents, such as the expense of purchasing kits, test blanks, computer programs, and paying per use fees. Also, all projective techniques provide an efficient way to collect a behavior sample outside of interview behavior. Psychologists’ time is valuable, but so is the client’s time, so that is another cost to be entered into cost-benefit analysis. Mastering one test that assesses an array of clinically relevant functions is efficient because it eliminates the need for many contentspecific tests. As a result, we can pick and choose more judiciously and master select instruments within an assessment battery, rather than misuse a large number of tests for all the potential purposes that a few broadband measures of personality address. As such, the next seven chapters are organized around the use of projective techniques in the assessment of several specific constructs pertinent in applied clinical work.

Of particular interest to psychodynamically oriented clinicians will be the chapter by Stricker and Gooen-Piels (Chapter 33) that updates a previous comprehensive review on the empirical study of projective assessment of object relations used with adults conducted by Stricker and Healey (1990) more than a decade ago. The authors begin with a discussion of the theory of object relations and describe ways in which this construct may be operationalized. They then present reliability and validity data for several projective measures of object relations. This body of empirical research supports both the construct of object relations and the accuracy of projective techniques to measure this construct. However, these authors also discuss problems that arise in attempting to assess constructs that are unconscious and make suggestions for future programmatic research designed to increase the ability to assess a range of object relations.

The chapter by Porcerelli and Hibbard (Chapter 34) provides a review of the three most prominent defense mechanism assessment scales for projective test data: the Lerner Defense Scale (Lerner, 1991), the Rorschach Defense Scale (Cooper, Perry, & Arnow, 1988), and the Defense Mechanisms Manual (Cramer, 1991). These scales have received empirical validation and can be easily utilized as part of a comprehensive psychological test battery. The chapter includes sections on the theory of defense mechanisms, a discussion of the relationship between defenses and psychopathology, and a comprehensive review of each scale. Reviews include a detailed description of each scale, the most up-to-date reliability and validity information, and a balanced discussion of strengths and limitations. This review demonstrates the increasing empirical support for the validity of defense mechanisms and emphasizes their importance in developing a dynamic understanding of personality strengths, adaptation, and psychopathology. The authors provide compelling evidence that the assessment of defense mechanisms is an indispensable part of any comprehensive personality test battery and include suggestions for the clinical use of these defense scales.

Building on a substantial body of previous research concerning interpersonal dependency (Bornstein, 1993, 1996, 1999), the chapter by Bornstein (Chapter 35) reviews the projective assessment of this construct. This review delineates the strengths and limitations of projective test variables assessing dependency as well as explores useful research and clinical applications. The chapter presents a broad definition of interpersonal dependency and the implications of the evolution of this construct for psychologists’ understanding of dependent personality traits. Projective instruments for assessing interpersonal dependency are evaluated, both individually and collectively. These projective instruments are then contrasted with self-report dependency measures. Strengths and limitations of both assessment methods are described. Finally, a conceptual framework for integrating projective and self-report test data is outlined, and future directions for research in projective dependency testing are discussed.

While no definitive borderline profile exists, projective assessment data from numerous instruments has proven to be useful in describing, diagnosing, and formulating treatment plans for patients with borderline psychopathology. The chapter by Blais and Bistis (Chapter 36) reviews the development of the borderline personality concept, from both the DSM and psychodynamic perspectives. The authors provide an updated review of the literature that is unique in that it organizes findings by the specific assessment instrument. The ability of projective assessment data to identify and describe patients with borderline psychopathology is delineated and focuses in particular upon the Rorschach, the TAT, and the Early Memories Test. The review of the literature suggests that borderline psychopathology can consistently be identified in projective assessment by (1) the systematic evaluation of thought quality (i.e., inner-outer boundary disturbance), (2) internalized object representations (i.e., malevolent), (3) degree and quality of aggression (intense, unmodulated, and destructive), and (4) level of defensive functioning (i.e., splitting). In addition, these authors discuss how a comprehensive assessment of projective data can help to establish the severity of a patient’s condition and can yield meaningful recommendations regarding treatment options.

Many individuals who seek treatment have experienced an emotionally, physically, and/or sexually traumatic event(s). The chapter by Armstrong and Kaser-Boyd (Chapter 37) reviews how projective tests may contribute to the understanding of trauma reactions and clinical issues related to trauma syndromes. This review begins with an overview of different theoretical and clinical perspectives on the nature of trauma. The chapter also provides a review of research findings for several variables of the Rorschach and TAT figural in the assessment of trauma and dissociation. While this chapter focuses more on the assessment of trauma reactions in civilian rather than military populations, it provides a complementary discussion to a recent review focusing on the projective assessment of stress syndromes in military personnel (Sloan, Arsenault, & Hilsenroth, 2001). Finally, a conceptual framework for integrating projective test data in relation to the assessment of trauma and dissociation is detailed and future directions for research in the projective assessment of traumatic sequelae are discussed.

The use of projective techniques in suicide risk assessment has a long and rich history. The chapter by Holdwick and Brzuskiewicz (Chapter 38) reviews the role that projective techniques can play in evaluating suicidal ideation and patient risk for self-harm, both as a proximal indicator of risk and in terms of distal risk prediction. While past reviews have focused on a limited number of projective methods (Rorschach, TAT), this chapter includes these prominent projective methods and less frequently used or researched techniques. Also unique to this review is the specific focus on the use of projective techniques for specific age groups (child, adolescent, adult). Empirical evidence for the use of projective techniques, specifically the Rorschach, in suicide risk assessment support their continued use in assisting clinicians who work with potentially suicidal patients. The Rorschach Comprehensive System’s Suicide Constellation (S-CON; Exner, 1993) remains the only, projective or self-report, scale that has been replicated as a predictive measure of future suicide or severe suicide attempt within 60 days of initial testing in a clinical sample (Exner & Wiley, 1977; Fowler, Piers, Hilsenroth, Holdwick, & Padawer, 2001). Also, this chapter presents information on newer scoring methods for the TAT with adults and Human Figure Drawings with children. Focus is also given to recently developed variables derived from projective techniques that may provide additional means for examining suicidal ideation and risk with patients. Issues regarding reliability, validity (concurrent, predictive, discriminant), and clinical utility for suicide assessment are discussed, as are limitations of these instruments.

Projective techniques not only provide an excellent means of assessing ideation or fantasies but they can also be useful in identifying formal disturbances in perception and thought organization. While several recent authors have provided empirical reviews of the validity of projective techniques in the assessment of thought disorder (Bellak & Abrams, 1997; Hilsenroth, Fowler, & Padawer, 1998; Jørgensen, Andersen, & Dam, 2000; W. Perry & Braff, 1998; W. Perry, Geyer, & Braff, 1999; Viglione, 1999; Viglione & Hilsenroth, 2001), the chapter by Kleiger (Chapter 39) seeks to organize conceptual and theoretical approaches to understanding the nature of thought disorder. Integrating contributions from the psychiatric, psychoanalytic, and psychological literature on thought disorder, Kleiger constructs a group of conceptual categories that can be accommodated to a range of projective instruments. The chapter offers a unique approach to thinking about the conceptual underpinnings of forms of disordered thought that can be used with a range of projective instruments for identifying thought disorder. The chapter concludes with a discussion of promising new avenues for empirical studies to develop formal scoring systems designed to capture various manifestations of disordered thinking using a variety of projective techniques.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND SETTINGS

Minassian and Perry (Chapter 40) review the use of projective personality instruments in the assessment of neurologically impaired individuals. These authors examine two distinct approaches to this topic. First, they discuss the traditional role of projective assessment in populations with neurological deficits, where the major effort is to understand personality organization. Specific populations such as head-injured patients, patients with cerebral dysfunctions, aging patients, dementia patients, and neurologically impaired children and adolescents are reviewed. These authors caution that some “personality” based interpretations of projective test performance may overlook the significance of underlying cognitive deficits and their impact on projective test behavior (Zilmer & Perry, 1996). Thus a “brain-behavior” approach to the examination of projective test data is warranted, where a primary focus of assessment is on the individual’s neuropsychological capabilities. In the second section of the chapter, Minassian and Perry propose that projective measures, such as the Rorschach Inkblot test, can be conceptualized from a cognitive perspective as complex problem-solving tasks. This section includes a review of the history of the Rorschach as a neuropsychological instrument and contributions of the Comprehensive System (CS) to the conceptualization of the Rorschach as a cognitive problem-solving task. The authors also include illustrations of how each phase of the Rorschach response process involves complex brain functions mediated by specific neural circuitry, the potential weaknesses of the CS in the arena of neuropsychological assessment, and the introduction of a “process” approach to examining neuropsychological deficits with projective instruments (W. Perry, Potterat, Auslander, Kaplan, & Jeste, 1996). Minassian and Perry conclude with suggestions regarding further integration of neuroscience, such as neuro-imaging, paired with performance on projective techniques, to further illustrate the important role that “personality” tests play in the assessment of neuropsychological functioning.

Although few studies have been conducted on the issue of malingering detection using projective personality tests since G. Perry and Kinder (1990) and Schretlen (1997) published their literature reviews, the aim of the chapter by Elhai, Kinder, and Frueh (Chapter 41) is to comprehensively discuss both the relevant literature and methodological issues of this topic. An introduction to the projective assessment of malingering is presented, followed by a review of the Rorschach’s ability to detect malingering, a review of additional projective tests used to assess malingering (including the TAT, Group Personality Projective Test [GPPT; Cassel & Brauchle, 1959] and SCT), a summary of findings, a discussion of methodological issues, and implications for clinical practice. Controlled studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of several indices to detect significant differences between simulator and comparison groups. In addition, the Rorschach has demonstrated an ability to produce valid protocols from subjects attempting to conceal psychological disturbance (i.e., emotional distress, self-critical ideation, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships) on self-report measures of personality (Ganellen, 1994). However, the studies utilizing projective tests in malingering assessment are not easily comparable, as they have examined a wide array of variables. Since no cutoff scores are available for projective tests in discriminating malingered from genuine protocols, these authors discuss salient limitations of using decision rules for the identification of malingering in clinician practice.

In addition to the recent general criticism of projective techniques, three recent journal articles have expressed specific concerns regarding the admissibility and use of data obtained from projective techniques in courtroom testimony (Garb, 1999; Grove & Barden, 1999; Wood, Nezworski, Stejskal, & McKinzey, 2001). Like the general attacks on projective techniques, these specific criticisms regarding forensic use have also been countered by several conceptual and empirical rebuttals (Gacono, 2002, in press; Gacono, Evans, & Viglione, in press; Jumes, Oropeza, Gray, & Gacono, 2002; Ritzler, Erard, & Pettigrew, 2002a, 2002b; Viglione & Hilsenroth, 2001). The chapter by McCann (Chapter 42) extends and updates (see McCann, 1998) this issue as well as provides further information for clinicians utilizing projective assessment methods in forensic settings. Several relevant issues are presented, including the legal standards for admissibility and professional standards for using psychological tests in legal settings. Evidentiary standards such as the Frye test (United States v. Frye, 1923), Daubert standard (1993), and new developments in Federal Rules of Evidence 702 (O’Conner & Krauss, 2001) are discussed, as well as professional standards that have been offered to guide the selection of assessment methods in forensic cases. Recognition is given to the fact that the use of projective methods has been controversial. The author reports that research on the patterns of psychological test use and a review of case law indicate that data gathered from projective methods are virtually always admitted into testimony. Also, projective methods appear to be widely used in forensic settings and courts have generally scrutinized the testimony of experts, rather than the individual methods employed. However, when expert testimony based on projective test data is ruled inadmissible, this decision is almost always based on the application or relevance of that testimony to the legal issue in question and not on the specific assessment instruments utilized by that expert. McCann concludes by offering some guidelines to assist practitioners in deciding whether to use projective methods in forensic settings, including the need to consider empirical support for the method and the amount and type of information such methods provide.

The chapter by Ritzler (Chapter 43) offers the first general review of empirical studies on the cultural relevance of projective personality assessment methods; specifically, he includes the Rorschach, apperception tests, and figure drawings. The first issue considered by Ritzler is possible differences in data due to the race of the individual. He reports no conclusive evidence of racial differences for any of the methods in this chapter. However, existing data are limited and primarily come from comparisons of samples of African Americans and Caucasian Americans from middle and upper socioeconomic levels. No studies have attempted to select participants from culturally distinct racial communities. A significant focus of this chapter is the “culture-free” and “culture-sensitive” aspects of the assessment methods. Culture-free methods are necessary to assess personality characteristics shared by all humans regardless of culture. Culture-sensitive methods are necessary to assess the influence of different cultures on personality functioning.

The author’s review of the Rorschach literature suggests that this measure essentially yields similar results across many different cultures. The few culture-sensitive findings for the Rorschach mostly come from early studies that compared modern cultures with primitive cultures. This conclusion is supported by current research that demonstrates very limited differences between nonpatient African American and Caucasian American adults matched on important demographic variables (Presley, Smith, Hilsenroth, & Exner, 2001). Finally, Meyer (2002) extends these findings by conducting a series of analyses to explore potential ethnic bias in Rorschach CS variables with a patient sample. After matching on several salient demographic variables, ethnicity revealed no significant findings and principal component analyses revealed no evidence of ethnic bias in the Rorschach’s internal structure. These findings are equivalent (Kline & Lachar, 1992; McNulty, Graham, Ben-Porath, & Stein, 1997; Neisser et al., 1996; Timbrook & Graham, 1994) or superior (Arbisi, Ben-Porath, & McNulty, 2002) to racial bias found within selfreport personality and cognitive assessment literature.

In contrast to the Rorschach, apperception tests yield results that suggest these methods are more culture sensitive than culture free. This is particularly true when the stimulus pictures are adjusted to include culture-specific features (Bellak & Abrams, 1997). Compared to the other methods, fewer studies have been conducted of the cultural relevance of figure drawings. However, the results that do exist are more equivocal for figure drawings than for the Rorschach or apperception tests. The limited data suggest that drawings may represent some middle ground between culture-free and culture-sensitive assessment.

Fischer, Georgievska, and Melczak (Chapter 44) present a useful approach to providing assessment feedback based on information derived from projective techniques. In collaborative assessment, the goal is to understand particular life events in everyday terms using assessment data as points of access to the client’s world. This collaborative approach to psychological assessment includes a broadened focus of attention beyond the scope of basic information gathering (Fischer, 1985/1994). In this therapeutic assessment model (Finn & Tonsager, 1997), the “assessors are committed to (a) developing and maintaining empathic connections with clients, (b) working collaboratively with clients to define individualized assessment goals, and (c) sharing and exploring assessment results with clients” (p. 378). Establishing a secure working alliance in the assessment phase of treatment may help address the despair, poor interpersonal relationships, feelings of aloneness, and experience of distress that frequently motivate patients to seek psychotherapy. In addition, by expanding the focus of assessment, both patient and clinician gain knowledge about treatment issues, which, in turn, provides the opportunity for a more genuine interaction during the assessment phase as well as in formal psychotherapy sessions. Early empirical findings examining this approach to psychological assessment have found that use of this model may decrease the number of patients who terminate treatment prematurely and may impact the patient’s experience of assessment feedback sessions (Ackerman, Hilsenroth, Baity, & Blagys, 2000). Additional advantages include decreases in symptomatic distress and increases in self-esteem and facilitation of the therapeutic alliance (Ackerman et al., 2000; Finn & Tonsager, 1992; Newman & Greenway, 1997). The improvement of the therapeutic alliance developed during the assessment was also later related to alliance early in psychotherapy (Ackerman et al., 2000).

This chapter provides an overview of collaborative practices, such as the exploration of both problematic and adaptive behavior. In addition, the authors describe how to discuss various actions, interactions, issues, and patterns of relating during the assessment process. Suggestions are made on how to individualize feedback to the client in terms of recognizing unsuccessful patterns and potentially adaptive alternatives. During this process, the assessor revises impressions and accesses real-life examples. Extensive excerpts from assessment sessions illustrate these practices with a variety of projective techniques. How projective techniques work and how they lend themselves to collaborative practices are also discussed. The concluding section points out the confluence of collaborative practices within several theories of clinical practice.

APPLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

A number of previous chapters in this volume have included information on the use and implications of various instruments, scales, and content areas with children and adolescents. In addition, this section contains three chapters that specifically address applications for the use of projective techniques with children and adolescents. In the first of these chapters, Westenberg, Hauser, and Cohn (Chapter 45) provide a review regarding the projective assessment of psychological development and social maturity with SCTs. A sentence completion test for measuring maturity in adults, the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT; Loevinger, 1985), was developed by Loevinger and her colleagues to assess the relevance of these constructs for clinical practice, organizational settings, and research protocols. Westenberg and his colleagues have recently developed a version of the WUSCT for use with children and youth (ages 8 and older), the Sentence Completion Test for Children and Youths (SCT-Y; Westenberg, Treffers, & Drewes, 1998). Both instruments are discussed in relation to Loevinger’s theory of personality development, which portrays personality growth as a series of developmental advances in impulse control, interpersonal relations, and conscious preoccupations. This chapter provides a comprehensive review of the WUSCT and recently developed SCT-Y. The authors provide an overview of the theoretical and empirical basis of the WUSCT and SCT-Y as measures of psychological and social maturity. The authors report research on these measures indicating excellent reliability, construct validity, and clinical utility. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the practical uses of these measures in clinical and organizational settings as well as recommendations for future research.

The chapter by Kelly (Chapter 46) outlines and evaluates prominent Rorschach and TAT content scales used to assess object representation measures in children and adolescents. The Urist (1977) Mutuality of Autonomy Scale (MOAS) and the Social Cognition and Object Relations Scale (SCORS) developed by Westen and colleagues (Westen, 1995; Westen, Lohr, Silk, Kerber, & Goodrich, 1989) are the primary scales of focus in this chapter. Also, the use of an early memory task, that is, the Comprehensive Early Memories Scoring System (CEMSS) developed by Bruhn (1981), in relation to use with children and adolescents is reviewed. Studies presenting reliability and validity measures for the MOAS, SCORS, and CEMSS are presented. This chapter by Kelly represents the first effort to comprehensively integrate the child and adolescent literature relating to object representation assessment utilizing projective techniques. Findings indicate impressive reliability and validity information pertaining to an evaluation of a child’s or an adolescent’s object representations.

The primary focus of the chapter by Russ (Chapter 47) is the measurement of the expression of affect in children’s pretend play. There is a specific focus on the Affect in Play Scale (APS; Russ, 1993). The APS was developed to meet the need for a reliable and valid scale that measures affective expression in pretend play for 6- to 10-year-old children. The chapter covers important areas such as: test description and development, psychometric characteristics, range of applicability and limitations, cross-cultural factors, accommodation for populations with disabilities, legal and ethical considerations, computerization, current research studies, use in clinical practice, and future directions. This review is distinctive in that the APS is placed in a projective assessment framework, recent research with the APS is included, and a wide range of clinically relevant issues concerning the use of the APS are considered. The main finding of the chapter is that the affective and cognitive processes measured by the APS are predictive of theoretically relevant criteria of creativity, coping, and adjustment. Both cognitive and affective processes are stable over a 5-year period. A summary of the extant research suggests that the APS measures processes that are important in child development, that they predict adaptive functioning in children, and that they are separate from what intelligence tests measure.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In addressing several different tests as well as specific content areas, populations, and issues, the chapters in this volume provide readers with an informed appreciation for the substantial but often overlooked research basis for the reliability, validity, and clinical utility of projective techniques. Interrater reliability of projective techniques has been found to be good (ICC/j !.60) to excellent (! .75) based on accepted psychometric standards (Fleiss, 1981; Fleiss & Cohen, 1973; Garb, 1998; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). Test-retest reliability data for projective techniques have been shown to be at least equivalent or superior to other psychological tests. Likewise these measures have demonstrated validity both broadly and in specific domains. Extensive normative data are available for several different scoring systems across a number of these techniques and the current collection of updated normative samples is under way for several measures. Also, projective techniques have been shown to provide reliable, valid, and clinically useful information across a range of ethnic diversity and internationally. Thus, several projective techniques, by virtue of the accumulated research, are now better prepared to stand the scrutiny of current psychometric standards. This is even more apparent when the same standards are applied equally to self-report, interview, neurological, and intelligence tests. The data from each of these assessment methods are used to provide a context in which to evaluate the efficacy of projective techniques.

In addition to providing a thorough, relevant review of the essential empirical literature, all of the contributions to this volume discuss the clinical utility of various measures in the context of a responsible psychological assessment process. This information derived from projective techniques can be utilized to address a broad range of relevant issues in psychological assessment. The chapters in this volume explore the interpretation and application of projective techniques in a complex, sophisticated, and integrated manner. Many of the authors describe such a configural, synthetic approach to projective test interpretation that is fundamental to the clinical/ actuarial method. In this method projective techniques provide an ecologically valid and informed understanding of interactive probabilities to increase accuracy of in vivo decision making in applied psychology.

In conclusion, it would seem prudent to encourage clinicians and researchers alike to employ multiple methods of psychological assessment, including projective techniques, and to utilize this information in a systematic and theoretically consistent fashion. Understanding the variety of options available for the measurement of personality and psychopathology is useful in order to compare and select among the various methods. In stark contrast to the opinions offered by Lilienfeld et al. (2000), the chapters in this volume support and extend previous research and applied clinical work utilizing projective techniques in psychological assessment. These contributions provide converging lines of evidence and support the use of projective techniques as a valuable method in the assessment of personality and psychopathology as well as contribute to a conceptual understanding of pertinent treatment issues. It is also important that psychologists continue to examine the manner in which projective techniques aid in understanding the idiographic richness and complexity of an individual. The results of such inquiry, utilizing both structural and theoretically derived variables, will undoubtedly provide important and meaningful information to facilitate psychological assessment and treatment.

REFERENCES

Ackerman, S., Hilsenroth, M., Baity, M., & Blagys, M. (2000). Interaction of therapeutic process and alliance during psychological assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75, 82–109.

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Arbisi, P., Ben-Porath, Y., & McNulty, J. (2002). A comparison of MMPI-2 validity in African American and Caucasian psychiatric inpatients. Psychological Assessment, 14, 3–15.

- Atkinson, L., Quarrington, B., Alp, I.E., & Cyr, J.J. (1986). Rorschach validity: An empirical approach to the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 360–362.

- Bellak, L., & Abrams, D. (1997). The TAT, the CAT, and the SAT in clinical use (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Block, J. (1995). A contrarian view of the five-factor approach to personality description. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 187–215.

- Bornstein, R.F. (1993). The dependent personality. New York: Guilford Press.

- Bornstein, R.F. (1996). Construct validity of the Rorschach Oral Dependency scale: 1967–1995. Psychological Assessment, 8, 200–205.

- Bornstein, R.F. (1999). Criterion validity of objective and projective dependency tests: A meta-analytic assessment of behavioral prediction. Psychological Assessment, 11, 48–57.

- Bornstein, R.F. (2002). A process-dissociation approach to objectiveprojective test score interrelationships. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78, 47–68.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Volume 3. Loss. New York: Basic Books.

- Bruhn, A. (1981). Children’s earliest memories: Their use in clinical practice. Journal of Personality Assessment, 45, 258–262.

- Buck, J. (1948). The H-T-P. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 4, 151–159.

- Burns, R., & Kaufman, S. (1970). Kinetic Family Drawings (K-F-D): An introduction to understanding children through kinetic drawings. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Butcher, J.N., Dahlstrom, W.G., Graham, J.R., Tellegen, A.M., & Kaemmer, B. (1989). MMPI-2: Manual for administration and scoring. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Camara, W., Nathan, J., & Puente, A. (2000). Psychological test usage: Implications in professional use. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31, 141–154.

- Campbell, D., & Fiske, D. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81–105.

- Cassel, R., & Brauchle, R. (1959). An assessment of the fakability of scores on the Group Personality Projective Test. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 95, 239–244.

- Clemence, A., & Handler, L. (2001). Psychological assessment on internship: A survey of training directors and their expectations for students. Journal of Personality Assessment, 76, 18–47.

- Colvin, R., Block, J., & Funder, D. (1995). Overly positive self evaluations and personality: Negative implications for mental health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 1152– 1162.

- Cooper, S., Perry, J., & Arnow, D. (1988). An empirical approach to the study of defense mechanisms: 1. Reliability and preliminary validity of the Rorschach Defense Scales. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 187–203.

- Cramer, P. (1991). The development of defense mechanisms: Theory, research, and assessment. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 113 S.Ct. 2786, (1993).

- Dawes, R.M. (1994). House of cards: Psychology and psychotherapy built on myth. New York: Free Press.

- Dozier, M., & Kobak, R. (1992). Psychophysiology in attachment interviews: Converging evidence for deactivating strategies. Child Development, 63, 1473–1480.

- Eisman, E., Dies, R., Finn, S.E., Eyde, L., Kay, G.G., Kubiszyn, T., et al. (2000). Problems and limitations in the use of psychological assessment in contemporary healthcare delivery. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31, 131–140.

- Erdberg, P., & Shaffer, T.W. (1999, July). International symposium on Rorschach nonpatient data: Findings from around the world. Symposium presented at the XVIth Congress of the International Rorschach Society, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Erdberg, P., & Shaffer, T.W. (2001, March). An international symposium on Rorschach nonpatient data: Worldwide findings. Symposium presented at the annual convention of the Society for Personality Assessment, Philadelphia, PA.

- Exner, J.E. (1989). Searching for projection in the Rorschach. Journal of Personality Assessment, 53, 520–536.

- Exner, J.E. (1991). The Rorschach: A comprehensive system: Volume 2. Interpretation (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Exner, J.E. (1993). The Rorschach: A comprehensive system: Volume 1. Basic foundations (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Exner, J.E. (1996). Critical bits and the Rorschach response process. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67, 464–477.

- Exner, J.E., & Wiley, J. (1977). Some Rorschach data concerning suicide. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 339–348.

- Eysenck, H. (1959). The Rorschach Inkblot test. In O.K. Buros (Ed.), The fifth mental measurements yearbook (pp. 276–278). Highland Park, NJ: Gryphon Press.

- Finn, S.E., & Tonsager, M.E. (1992). Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to college students awaiting therapy. Psychological Assessment, 4, 278–287.

- Finn, S.E., & Tonsager, M.E. (1997). Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: Complementary paradigms. Psychological Assessment, 9, 374–385.

- Fischer, C.T. (1985/1994). Individualized psychological assessment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Fleiss, J. (1981). Statistical methods for rates and proportions (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Fleiss, J., & Cohen, J. (1973). The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33, 613–619.

- Fowler, C., Piers, C., Hilsenroth, M., Holdwick, D., & Padawer, R. (2001). Assessing risk factors for various degrees of suicidal activity: The Rorschach Suicide Constellation (S-CON). Journal of Personality Assessment, 76, 333–351.

- Frank, L.K. (1939). Projective methods for the study of personality. Journal of Psychology, 8, 389–413.

- Funder, D.C. (1997). The personality puzzle. New York: Norton.

- Gacono, C. (2002). Why there is a need for the personality assessment of offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 46, 271–273.

- Gacono, C. (in press). Introduction to a special series: Forensic psychodiagnostic testing. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice.

- Gacono, C., Evans, B., & Viglione, D. (in press). The Rorschach in forensic practice. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice.

- Ganellen, R. (1994). Attempting to conceal psychological disturbance: MMPI defensive response sets and the Rorschach. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 423–437.

- Garb, H.N. (1998). Studying the clinician: Judgment research and psychological assessment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Garb, H.N. (1999). Call for a moratorium on the use of the Rorschach Inkblot test in clinical and forensic settings. Assessment, 6, 313–315.

- Garb, H.N., Florio, C.M., & Grove, W.M. (1998). The validity of the Rorschach and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: Results from meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 9, 402–404.

- Garb, H.N., Wood, J.M., Nezworski, M.T., Grove, W.M., & Stejskal, W.J. (2001). Towards a resolution of the Rorschach controversy. Psychological Assessment, 13, 433–448.

- George, C., West, M., & Pettem, O. (1999). The Adult Attachment Projective: Disorganization of adult attachment at the level of representation. In J. Solomon & C. George (Eds.), Attachment disorganization (pp. 462–507). New York: Guilford Press.

- Grove, W.M., & Barden, R.C. (1999). Protecting the integrity of the legal system: The admissibility of testimony from mental health experts under Daubert/Kumho analyses. Psychology, Public Policy, and the Law, 5, 224–242.

- Hiller, J.B., Rosenthal, R., Bornstein, R.F., Berry, D.T.R., & Brunell-Neuleib, S. (1999). A comparative meta-analysis of Rorschach and MMPI validity. Psychological Assessment, 11, 278–296.

- Hilsenroth, M.J., Fowler, C.J., & Padawer, J.R. (1998). The Rorschach Schizophrenia Index (SCZI): An examination of reliability, validity, and diagnostic efficiency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 70, 514–534.

- Hunsley, J., & Bailey, J.M. (1999). The clinical utility of the Rorschach: Unfulfilled promises and an uncertain future. Psychological Assessment, 11, 266–277.

- Hunsley, J., & Bailey, J.M. (2001). Wither the Rorschach? An analysis of the evidence. Psychological Assessment, 13, 472–485.

- Jackson, D. (1971). The dynamics of structured personality tests. Psychological Review, 78, 229–248.

- Jensen, A. (1965). The Rorschach Inkblot test. In O.K. Buros (Ed.), The sixth mental measurements yearbook (pp. 501–509). Highland Park, NJ: Gryphon Press.

- John, O., & Robins, R. (1994). Accuracy and bias in self-perception: Individual differences in self-enhancement and the role of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 206–219.

- Jørgensen, K., Andersen, T.J., & Dam, H. (2000). The diagnostic efficiency of the Rorschach Depression Index and the Schizophrenia Index: A review. Assessment, 7, 259–280.

- Jumes, M., Oropeza, P., Gray, B., & Gacono, C. (2002). Use of the Rorschach in forensic settings for treatment planning and monitoring. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 46, 294–307.

- Kline, R.B., & Lachar, D. (1992). Evaluation of age, sex, and race bias in the Personality Inventory for Children (PIC). Psychological Assessment, 4, 333–339.

- Leary, T. (1957). Interpersonal diagnosis of personality. New York: Ronald.

- Lerner, P. (1991). Psychoanalytic theory and the Rorschach. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Lerner, P. (1992). Toward an experiential psychoanalytic approach to the Rorschach. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 56, 451–464.

- Lilienfeld, S.O., Wood, J.M., & Garb, H.N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1, 27–66.

- Loevinger, J. (1985). Revision of the Sentence Completion Test for Ego Development. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 281–311.

- Machover, K. (1949). Personality projection in the drawing of the human figure. Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas.

- McCann, J.T. (1998). Defending the Rorschach in court: An analysis of admissibility using legal and professional standards. Journal of Personality Assessment, 70, 125–144.

- McClelland, D.C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96, 690–702.

- McNulty, J.L., Graham, J.R., Ben-Porath, Y., & Stein, L.A.R. (1997). Comparative validity of MMPI-2 scores of African American and Caucasian mental health center clients. Psychological Assessment, 9, 464–470.

- Meyer, G.J. (1997a). Assessing reliability: Critical correlations for a critical examination of the Rorschach Comprehensive System. Psychological Assessment, 9, 480–489.

- Meyer, G.J. (1997b). Thinking clearly about reliability: More critical correlations regarding the Rorschach Comprehensive System. Psychological Assessment, 9, 495–498.

- Meyer, G.J. (2000). On the science of Rorschach research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75, 46–81.

- Meyer, G.J. (2001). Evidence to correct misperceptions about Rorschach norms. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8, 389–396.

- Meyer, G.J. (2002). Exploring possible ethnic differences and bias in the Rorschach Comprehensive System. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78, 104–129.

- Meyer, G.J., & Archer, R. (2001). The hard science of Rorschach research: What do we know and where do we go? Psychological Assessment, 13, 486–502.

- Meyer, G.J., Finn, S.E., Eyde, L., Kay, G.G., Moreland, K.L., Dies, R.R., et al. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues. American Psychologist, 56, 128–165.

- Meyer, G.J., & Handler, L. (1997). The ability of the Rorschach to predict subsequent outcome: A meta-analysis of the Rorschach Prognostic Rating Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69, 1–38.

- Meyer, G.J., Hilsenroth, M., Baxter, D., Exner, J., Fowler, C., Piers, C., et al. (2002). An examination of interrater reliability for scoring the Rorschach Comprehensive System in eight data sets. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78, 219–274.

- Murray, H.A. (1943). Thematic Apperception Test. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard, T.J., Jr., Boykin, A.W., Brody, N., Ceci, S.J., et al. (1996). Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns. American Psychologist, 51, 77–101.

- Newman, M.L., & Greenway, P. (1997). Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to clients at a university counseling service: A collaborative approach. Psychological Assessment, 9, 122–131.

- O’Conner, M., & Krauss, D. (2001). Legal update: New developments in Rule 702. APLS News, 21, 1–4, 18.

- Ozer, D.J. (1999). Four principles for personality assessment. In L.A. Pervin & O.P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed.; pp. 671–686). New York: Guilford Press.

- Parker, K.C.H., Hanson, R.K., & Hunsley, J. (1988). MMPI, Rorschach, and WAIS: A meta-analytic comparison of reliability, stability, and validity. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 367–373.

- Perry, G., & Kinder, W. (1990). Susceptibility of the Rorschach to malingering: A critical review. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54, 47–57.

- Perry, W. (2001). Incremental validity of the Ego Impairment Index: A re-examination of Dawes (1999). Psychological Assessment, 13, 403–407.

- Perry, W., & Braff, D. (1998). A multimethod approach to assessing perseverations in schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia Research, 33, 69–77.

- Perry, W., Geyer, M.A., & Braff, D.L. (1999). Sensorimotor gating and thought disturbance measured in close temporal proximity in schizophrenic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 277–281.

- Perry, W., Potterat, E.G., Auslander, L., Kaplan, E., & Jeste, D. (1996). A neuropsychological approach to the Rorschach in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Assessment, 3, 351–363.

- Peterson, D. (1995). The reflective educator. American Psychologist, 50, 975–983.

- Presley, G., Smith, C., Hilsenroth, M., & Exner, J. (2001). Rorschach validity with African Americans. Journal of Personality Assessment, 77, 491–507.

- Rapaport, D., Gill, M., & Schafer, R. (1945). Diagnostic psychological testing: The theory, statistical evaluation, and diagnostic application of a battery of tests. Chicago: Year Book. (Revised Ed., 1968, R.R. Holt, Ed.).

- Raskin, J. (2001). Constructivism and the projective assessment of meaning in Rorschach administration. Journal of Personality Assessment, 77, 139–161.

- Ritzler, B., Erard, R., & Pettigrew, G. (2002a). Protecting the integrity of Rorschach expert witnesses: A reply to Grove and Barden (1999) re: The admissibility of testimony under Daubert/Kumho analysis. Psychology, Public Policy, and the Law, 8, 201–215.

- Ritzler, B., Erard, R., & Pettigrew, G. (2002b). A final reply to Grove and Barden: The relevance of the Rorschach Comprehensive system for expert testimony. Psychology, Public Policy, and the Law, 8, 235–246.

- Rorschach, H. (1921/1942). Psychodiagnostics: A diagnostic test based on perception. New York: Grune & Stratton.

- Rosenthal, R., Hiller, J.B., Bornstein, R.F., Berry, D.T.R., & Brunell-Neuleib, S. (2001). Meta-analytic methods, the Rorschach, and the MMPI. Psychological Assessment, 13, 449–451.

- Rossini, E., & Moretti, R. (1997). Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) interpretation: Practice recommendations from a survey of clinical psychology doctoral programs accredited by the American Psychological Association. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 28, 393–398.

- Rotter, J., Lah, M., & Rafferty, J. (1992). Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace.

- Russ, S. (1993). Affect and creativity: The role of affect and play in the creative process. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Schachtel, E. (1966). Experiential foundations of Rorschach’s test. New York: Basic Books.

- Schretlen, D. (1997). Dissimulation on the Rorschach and other projective measures. In R. Rogers (Ed.), Clinical assessment of malingering and deception (2nd ed.; pp. 208–222). New York: Guilford Press.

- Shedler, J., Mayman, M., & Manis, M. (1993). The illusion of mental health. American Psychologist, 48, 1117–1131.

- Shrout, P.E., & Fliess, J.L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 420–428.

- Sloan, P., Arsenault, L., & Hilsenroth, M. (2001). Use of the Rorschach in assessment of war-related stress in military personnel. Rorschachiana (Journal of the International Rorschach and Projective Techniques Society), 25, 86–122.

- Stedman, J., Hatch, J., & Schoenfeld, L. (2000). Preinternship preparation in psychological testing and psychotherapy: What internship directors say they expect. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31, 321–326.

- Stricker, G., & Healey, B.J. (1990). Projective assessment of object relations: A review of the empirical literature. Psychological Assessment, 2, 219–230.

- Timbrook, R.E., & Graham, J.R. (1994). Ethnic differences on the MMPI? Psychological Assessment, 6, 212–217.

- United States v. Frye, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir., 1923).

- Urist, J. (1977). The Rorschach test and the assessment of object relations. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 3–9.

- Viglione, D.J. (1999). A review of recent research addressing the utility of the Rorschach. Psychological Assessment, 11, 251–265.

- Viglione, D., & Hilsenroth, M. (2001). The Rorschach: Facts, fictions, and future. Psychological Assessment, 13, 452–471.

- Wagner, E. (1983). The Hand Test manual (rev. ed.). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

- Wechsler, D. (1997). WAIS-III/WMS-III technical manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Weinberger, D. (1995). The construct validity of repressive coping style. In J.L. Singer (Ed.), Repression and dissociation: Implications for personality theory, psychopathology, and health (pp. 337–388). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Weiner, I.B. (1996). Some observations on the validity of the Rorschach Inkblot Method. Psychological Assessment, 8, 206–213.

- Weiner, I.B. (2001). Advancing the science of psychological assessment: The Rorschach Inkblot Method as exemplar. Psychological Assessment, 13, 423–432.

- Westen, D. (1995). Social Cognition and Object Relations Scale: Q-sort for projective stories (SCORS-Q). Unpublished manuscript, Cambridge Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA.

- Westen, D., Lohr, N., Silk, K., Kerber, K., & Goodrich, S. (1989). Object relations and social cognition TAT scoring manual (4th ed.). Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Westenberg, P., Treffers, P., & Drewes, M. (1998). A new version of the WUSCT: The Sentence Completion Test for Children and Youths (SCT-Y). In J. Loevinger (Ed.), Technical foundations for measuring ego development (pp. 81–89). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Widiger, T., & Frances, A. (1987). Interviews and inventories for the measurement of personality disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 7, 49–75.

- Wood, J.M., Nezworski, M.T., & Stejskal, W.J. (1996). The Comprehensive System for the Rorschach: A critical examination. Psychological Science, 7, 3–10.

- Wood, J.M., Nezworski, M.T., Stejskal, W.J., & McKinzey, R.K. (2001). Problems of the Comprehensive System for the Rorschach in forensic settings: Recent developments. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 1, 89–103.

- Zilmer, E., & Perry, W. (1996). Cognitive-neuropsychological abilities and related psychological disturbance: A factor model of neuropsychological, Rorschach and MMPI indices. Assessment, 3, 209–224.

CHAPTER 24 Projective Tests: The Nature of the Task

MARTIN LEICHTMAN

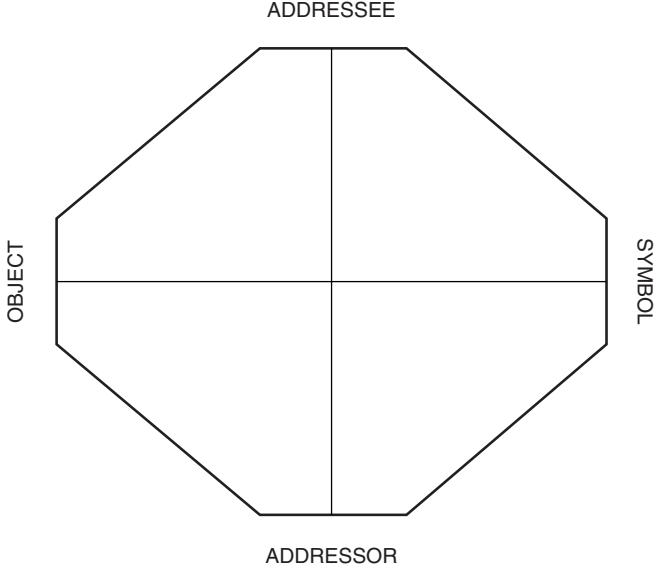

INTRODUCTION 297 WHAT ARE “PROJECTIVE” TESTS? 298 Projection 298 Apperception 299 Alternative Processes 300 Empirical Definitions 301 THE PROJECTIVE TASK 302 THE STRUCTURE OF THE REPRESENTATIONAL PROCESS 303 The Symbol Situation 303

Addressor and Addressee 304 The Medium or Vehicle 306 The Referent 308 CONCLUSION 309 Similarities and Differences Among Projective Tasks 309 Approaches to Interpretation 309 Strengths and Limitations 310 The Future of Projective Tests 311 REFERENCES 312

INTRODUCTION